While many educators do see relationships as the answer to most educational questions, Dr. Gustafson reminds us of two things. One, that we must be intentional about investing in those relationships, and two, that relationships cannot be the answer without relevance. He states, “I don’t think it’s a coincidence the same teachers who build deeper relationships with students are also able to make the learning process meaningful to individual learners. They are gifted noticers who prioritize listening, asking open-ended questions, and learning about students’ interests outside of school. These teachers understand the importance of who. This helps them ensure their approach is always relevant.” Staying relevant means that we must let go of “this is the way it has always been done” from time to time (or more often than that) and give ourselves the freedom to let go of old routines, push boundaries, and think outside the box about the ways to best interact with out students. Again, as whole learners. As Dr. Gustafson shares, “We need to enter into our students’ world, wherever they might be, and seek to understand who we can become to serve them better.” This is our moral obligation to the youth we serve.

|

The third and final chapter of the “Moral Foundation of Education” portion of Gustafson’s book echoes a now familiar, but slightly varied version of his definition. “The moral foundation of education is built upon relationships and learning that lasts.” Relationships. The silver bullet of education. I have yet to find an educator who doesn’t give the importance of relationships as the answer to nearly any problem. While it seems like a simple answer, at its core, relationship building is an unending task as we work to build a trust and understanding with each and every student and staff member and community member, and is daunting, to say the least. Gustafson points out that “the most gifted educators connect in a manner that’s meaningful to the other person.” You must connect with people over something that is important to them, not you, which requires an investment of time that may be easy to dismiss. However its benefits will pay off tenfold in the common culture and community that embrace each other before embarking on new learning endeavors.

While many educators do see relationships as the answer to most educational questions, Dr. Gustafson reminds us of two things. One, that we must be intentional about investing in those relationships, and two, that relationships cannot be the answer without relevance. He states, “I don’t think it’s a coincidence the same teachers who build deeper relationships with students are also able to make the learning process meaningful to individual learners. They are gifted noticers who prioritize listening, asking open-ended questions, and learning about students’ interests outside of school. These teachers understand the importance of who. This helps them ensure their approach is always relevant.” Staying relevant means that we must let go of “this is the way it has always been done” from time to time (or more often than that) and give ourselves the freedom to let go of old routines, push boundaries, and think outside the box about the ways to best interact with out students. Again, as whole learners. As Dr. Gustafson shares, “We need to enter into our students’ world, wherever they might be, and seek to understand who we can become to serve them better.” This is our moral obligation to the youth we serve.

0 Comments

Part 3 of my blog series reflecting on Dr. Brad Gustafson's new book, Reclaiming Our Calling

Part of our duty in our quest to secure our moral high ground, our quest to see every child as a whole learner, is to help outsiders see school as more than a structure for surface level content learning. On its face, “surface level learning alone is inadequate in preparing students for an unknown future.” While some may argue that content is for school and character is for home, this is not the reality we live in. If we understand school as a place where children go to prepare for their future, we must take into account that we are on a technological precipice that makes our future utterly unpredictable. To prepare students for the unpredictable we must equip them with skills that transcend content knowledge. We must equip them with the skills to question and advocate and empathize and build relationships. They must be able to tap into their creativity and be familiar with the determination it takes to work through productive struggle. These are not easy to teach. But as Gustafson points out, “We should be operating with our feet firmly planted on the moral foundation of teaching instead of leaning toward the things that are easiest to measure. The moral foundation of teaching is our high ground, and we need to stand firm on it.” When think about our own moral high ground and ethical obligations to our students, Dr. Gustafson suggests writing them down as a reminder of what we want to stand firm on. My own code of ethics is posted on my blog because of this. Reminders of the work we know we must do are helpful ways to make sure that you are following through with purpose. “Seeing students as whole learners - lifelong learners - is the moral foundation of education. No program or policy that prioritizes short-term gains should ever prevail over learning that lasts.” The moral foundation of education is seeing students as whole learners. Not numbers. Not test scores. Not weighted seats. I truly believe that it is with this conviction that each of us enters this noble profession. However, it is not long before stress, policy, mandates, and a lack of resources find many jaded and trying to get by while meeting the requirements and calls for improvement by those that have little understanding of how things like ESSA designations and School Report Cards are calculated. It is easy to succumb to the external pressures that lead otherwise passionate educators down a path of standardization and one-size-fits-all curriculum meant to better align to test scores. It is not to be said that student achievement isn’t important, but if the moral foundation of our profession is, as Dr. Gustafson states, seeing students as whole, lifelong learners, then we must do a better job of communicating the variables that are not seen in these mass-produced formulas and weighted criteria that dictate the perceived “success” and “failure” of a school district.

What we must value, as Dr. Gustafson illustrates in his portrait of a classmate named Joey, is the way our students feel about themselves. We must value our ability to see in our students a potential that they may not recognize for themselves. We must seek to help each and every student find the light within them and empower them to grow as individuals. This must be true for ALL students. Obstacles will present themselves. Dr. Gustafson reminds us that we do not all have the same priorities or philosophies about what is best for children. We will run into challenging co-workers and supervisors. There will always be difficult situations. But he also states that, “Adversity can always teach us something if we let it. Vulnerability and humility accelerate our learning, but even the smallest excuse or deflection will stunt our growth.” It is our duty as educators to identify priorities and common goals; “to help students achieve at high levels while seeing them as whole learners.” I started a new book in the new year and used it for some reflections for my latest assignments in my principal licensure program. I felt passionately enough about the topics that I wanted to share some of them. Today's post looks at just the prologue.

In Brad Gustafson’s book, “Reclaiming Our Calling” he introduces four passions of the education profession: 1) The Moral Foundation of Education, 2) The Heart of Education, 3) The Mind of Education, and 4) The Hope of Education. In the opening of the book he reminds us that there are many people who think they are well-positioned to evaluate and critique the work of education based on a single credential: they have been through the education system. However, Gustafson notes that it doesn’t matter who those people are, “the way they are trying to define our work doesn’t always position us to do immense good for the students we serve,” and as such he challenges us to think about how we can take back our profession. As we worked our way through the ethics standard for class, one piece of advice seemed to be the golden rule: do what you need to do with the best interest of kids as your guide post. We all know the struggle that afflicts modern schools; the struggle between academia and student well-being. Gustafson’s prologue serves as a reminder that we cannot ignore accountability, but “what we need to confront are the destructive testing influences that aren’t serving students.” The opening words of his work serve as a challenge to the status quo of high stakes testing, and as a reminder to put the child before the test. He identifies “Passion I” in his book as the moral foundation because, “We already know doing what’s best for kids is an ethical obligation that extends far beyond preparing students to do well on testing day.” While I think most (or all) of us would hold this to be true, it sometimes comes at odds against district policy, community/parent focus, and state and federal regulations. It is our job as educators to remind ourselves and our stakeholders that the whole child is first and foremost in every step of the way. I am on the brink of completing my work in the ethics standards of my principal program. While a standard about ethics initially seemed to me to be the least exciting of the bunch, it was hardly the dry, procedural information I anticipated needing to check a box. The opportunity to dig into the murky waters of decision making and educational scenarios that happen each and every day around the globe turned out to be one of the experiences that I believe will best benefit me and my future school(s). Much like police officers are trained to think in theoretical situational responses, educators must also be practiced and aware of their options, deficits, and challenges. From the inspirational, to the practical, to the practice scenarios, this standard illustrated the need for all of us to have a firm grasp on procedure, policy, law, and a little bit of creativity.

In writing my own code of ethics I really wanted to illuminate that we are on the cusp of some really potentially history-making scenarios. As we contemplate gender equality, gender fluidity, the re-segregation of our schools, and what it means to be accepting and tolerant in an era of increased hate crimes, we must balance that with what it means to live in a geographic region that holds strongly to down-home, “traditional” values. It is not unlikely that any of us in this cohort will face one or more of these issues in our careers as educational leaders. It is also imperative to note that while not every issue that comes across our desks may be one of these “high stakes” hot topics, the issue very likely is high stakes to someone; to some child. Whether it be adopting a new curriculum or deciding whether or not to hand down a suspension, our actions have impact that have lasting effects on the children we serve. Holding ourselves in the highest regard of ethical practice is essential to the well-being of those children. Equity. A word that has resurfaced in education as another hot topic on the verge of becoming a buzz word (or maybe already has). I was at a workshop recently and I heard phrases like "our district does a lot with equity, so I guess I'm doing it?" and "new teachers have enough on their plate, adding in the idea of equity as another thing might be too overwhelming." Stop. Stop it right now. At this point I'm wanting to jump out of my seat with my decoder ring yelling, "Activist allies unite!" to my friend across the room who I know would back me up in this conversation. All this after I had just shared a story about how inspiring and powerful it had been to hear a group of 4th, 5th, and 6th grade students bravely ask questions and share insights into the role race plays in our past and current society. Friends, equity cannot go the way of the buzz word. Equity is not something we do. It is embedded in the very foundation of who we are. It is embedded in the interactions we have with our children; our students.

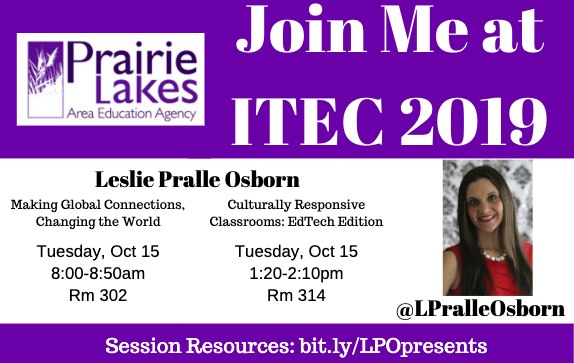

Equity, by definition, is fairness. It is justness. It is giving each and every child regardless of race, class, gender, religion, ability, citizenship status, or sexual orientation - a chance to succeed. And equity, in practice, means that all kids do not get the same thing because they do not all need the same thing. Equity in our schools means that we have created a space where all students are seen and where all students' stories are valued. Each and every one. I've been reading Dr. Brad Gustafson's new book, "Reclaiming Our Calling," and in it he says, "We need to enter into our students' world, wherever they might be, and seek to understand who we can become to serve them better." I would add to that WHOever they might be. He says we must "seek to understand who we can become to serve them better." Who we can become. How can we change, what can we intentionally do to better situate ourselves to build relationships and empathy and understanding for these children that we serve? Especially the ones that come from a different background than we do, a different type of family than we do, a different way of life than we do? If this premise, the idea of serving each and every kid no matter who they are to the best of our ability is not at the foundation of who we are as educators, I would argue that you are in the wrong profession. Equity is not something we do. It is not a professional learning series. It is not a workshop. It is not a box to be checked. Equity is a way of being. It is making sure ALL your kids have what they need to learn. It is not one more thing, it is THE thing.  When my husband moved into my house I went through a lot of transition in trying to make it OUR home. We painted some walls and I picked out some new decorations that spoke more to his taste (aka GIANT Batman wall-hanging). When our youngest daughter was born I made it one of my top priorities to ensure that she sees herself in our home. She won't often see herself in standard curriculum, in the teachers in her classrooms (80+% of all US public school teachers are white), or in the businesses of our community, so I was going to make *dang* sure that she sees herself in our home. Step one: Updating photos on the walls, of course, so she could literally see herself. That one was easy because there are hundreds of pictures of new babies - although who prints anymore, right? But seriously... One of the things that has become an "easy" win for me was starting with books. I love books, so with a little Googling and a whole lot of Amazon-ing, making intentional choices about the books that I put on the shelves for our family was a pretty painless first step. There are a million book lists out there, but I recommend checking out publisher Lee & Low publishing or try some of the book lists recommended by social justice educator and author Debby Irving. A couple of my personal favorites are The Day You Begin, by Jacqueline Woodson and The Hate U Give, by Angie Thomas. My next step was to add to our art collection. We have pieces that celebrate our family or have sentimental value, of course, but I began to take note of black artists who really inspired me through their work and word art that frames the beliefs we hold in our family. I fell in love with the "Golden Dancer" piece by Dexter Griffin at Shon's grandmother's house and purchased one from our home. Eventually this extended into holidays. We kept the pieces that meant something to us as individuals, but we don't *only* have white Christian normative Christmas decorations. We've talked about Kwanzaa, from which a kinara sits as my kitchen table centerpiece awaiting our celebratory dinner. Last year my aunt and uncle were accidentally shipped a chocolate Santa with an order that they've made, so they passed it on to us. All year long "black Santa" sat in a place of honor on our book shelf until finally Shon let the kids enjoy the chocolate in October. I replaced chocolate Santa with a beautiful painting for my wall this year. On the flip side, we also have straw Swedish ornaments passed on to me from my grandmother. For me it's not about putting up African-American art and images for the sake of having African-American art, but choosing pieces that have meaning to celebrate the diversity of our home. The final, more difficult and less tangible shift we've tried to make has been around how we have switched our conversations. We discuss hard issues, we try to understand multiple perspectives around issues. We're careful about our jokes and we name actions and words that are not okay (from ourselves and from others). I may not agree with much (most) of the actions of some of our elected officials, but we try to provide context for why others might agree. I want my children, all four of my children, to question - their beliefs, those around them, and the status quo. So why am I sharing all this on my professional blog? Because these are changes you can make in your classroom. Ask families what artists and books they have in their homes. What holidays do they celebrate? How can we diversify our bookshelves and bulletin boards? How do we make sure we're going beyond the surface? I hope my daughter doesn't study only MLK Jr and Rosa Parks for the first eight years of her education. I want her to see herself in the texts and the pictures on the walls. And likewise, I want my white children to experience more than just their white culture. I want them to know names of activists like Kwame Ture (you may know him as Stokely Carmichael, but you may not know him at all) and read the works of Ta-Nehisi Coates (one of my favorite contemporary writers). I want them to see the world for what it is, not what we think it might be because of our geographic location and homogenous populations. I want them to have an intelligent debate about why Colin Kaepernick took a knee - and know and understand the *real* reasons. I made these changes for my children at home, but when you're a teacher they are ALL "your" kids. They all deserve to see themselves, and even in our most homogenous schools, we're doing kids a disservice if we are not providing them with windows into the lives of people with different experiences from their own. Ready to make some shifts but not sure how? Check out the resource page I've started building, reach out - I'd love to come share or connect you with a person in your area, or check out this site for celebrating Multicultural Children's Book Day! While I understand that we don't want to reduce multicultural literature to one day, there are some fantastic resources to get you started ahead of and beyond Jan 25, 2019! And finally, I'd love to have you share your own ideas and shifts in the comments!  It's been nearly a year since I shared my journey into making sense of the role race plays in our society. You don't notice as it happens, but when I look back on 2018 I see that I am not the same person that started this journey. I am so, so happy to share that. Over the last year I've immersed myself in documentaries and docu-series and "based on a true story"-s and "this is fiction but you know it's reality" programming from Netflix and Hulu and Amazon (we have a lot of subscription services). Over the last year I have explored Selma and the Central Park Five and Trayvon Martin and Ferguson and Chicago Public Schools and the "new" KKK. There are too many areas to list. Over the last year I have soaked in the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates (fan-girling), James Baldwin, Jonathan Kozol, Beverly Daniel Tatum (another favorite), Michelle Alexander, Austin Channing Brown (she's so real!), and so many more. Over the last year I've shared my experiences and new learning with friends and family and educators and bosses and the public world of social media. I've found the people who share a part of my soul, I've made people uncomfortable, I've received pushback. And over the last year I've reaffirmed what I sort of already knew. That none of this is about me. I have loved my learning journey and can't wait to continue down this path, but it's not about what I learn. It's about what I do with it. I can stock my bookshelves with multicultural children's book and authors speaking to equity and culturally responsive teaching and someday I might even actually make it through the stack of books by my bed, but it doesn't matter if it doesn't translate to the classroom. I can be as "woke" as I want to think I am, but if I can't name and call out racism when I see and hear it, it doesn't matter. I can collect notebooks full of classroom shifts and hundreds of bookmarks to websites to help others gain understanding, but if I don't bring it into classrooms it doesn't matter. The learning is a huge part of the journey, but my 2019 will be a year of action. My 2019 starts with two Teaching Tolerance workshops in January. My 2019 includes working with kids to understand the historical and societal complexities of "blackface." My 2019 will put more diverse texts in the classrooms that I serve. Because students deserve these conversations and the resources and the opportunity to make sense of this complex world we live in. My 2019 isn't about me, it's about reaching out to every kid every day and inspiring others to do the same. We make a lot of assumptions in our lives.

I assumed that the happy, sheltered bubble I lived in was reality. I assumed that I treated all my students the same. I assumed that we lived in an evolved society where color didn’t matter. I assumed the “racists” were the outliers. I assumed my own kids would not deal with major racially charged conflicts. Then, in what sometimes seems like the blink of an eye, the bubble popped. Reality broken. Eyes opened. Life changed. I remember when my world first collided with reality. We were waiting to get into a club in Minnesota and the bouncer wouldn’t let my (then) boyfriend in because he didn’t meet the dress code. Our white friend had just been let in wearing the exact same outfit. A racial slur (that I didn’t hear) was muttered by a bystander on our way out the door, and all bets were off. I didn’t understand the anger. I didn’t understand what had happened. In my defense, I didn’t hear what had actually happened, but in reality, I just didn’t get it - because that wasn’t MY reality. “I don’t see color,” is a phrase I’m sure I said at some point in my life, probably more than once. And then I realized that I didn’t see color because I didn’t have to - until very recently, that is. Nobody had ever watched my family as we sat down to eat at the local fast food restaurant. Nobody had ever introduced themselves to my significant other by explaining the difference between “black men” and “n*****s.” Nobody had ever blogged about my inability to parent properly because my child’s hair is different than mine. Nobody had ever told me my child was beautiful simply because of her genetic makeup. Don’t get me wrong, my kids are adorable, but people don’t usually cite their race as the reason. But trust me, I’ve said this, too. I’m not exempt from bias because I’m marrying a black man. What assumptions do you make about your students? About their families? Do you make assumptions based on older siblings? On parents that you had when they were in school? About the part of town they come from or the state they moved from? We want education and opportunities and authenticity for all kids. But can we offer that if we don’t strive to understand the realities of all kids? If we don’t help them see the reality of others? We were discussing trade and culture in South America in Geography class one day. At one point I asked the students if we would be having the same conversation if Carlos had been there that day. The room fell silent. Reality had just shifted. Let’s be honest. We are all happily unaware of our biases because it makes life easier. The world was a happier place when I got to view it through my white, middle class lens. “That doesn’t happen here.” Until that eye-opening moment reality smacks us in the face. The first thirty years of my life are no longer my reality. Will people see my youngest daughter, with her caramel complexion and dark hair and eyes and make assumptions? Will they assume her mother has a master’s degree and license in administration, that her father has a degree in physical therapy and works as a production supervisor? Will they assume that the young white boy teasing her and walking beside her is her fiercest protector? Can I assume that my biracial daughter will get the same opportunities as my white sons? Because I’ll be honest with you, I am facing my most difficult parenting dilemma to date. I would love to think that my parenting style is my parenting style. But I am raising kids for two very different worlds - and hopefully, if I’m lucky, raising my kids to see a clear picture of the real world. I won’t ever claim to have it all together. My journey toward understanding any of this is just beginning, and my journey is just that - mine. But as I think about how I raise my own kids and how I educate others, I fall back on my new mantra. No longer are they things that are done to me, “Broken Reality. Eyes Opened. Life Changed.” It’s about what I strive to do for myself and for others. “Break Reality. Open Eyes. Create Change.” I can only break reality by forcing myself to step outside my own comfort zone. I can only help people identify their biases by confronting and being honest about my own. I can only create change by modeling that change myself. This is what I want for my family; for my students; for my teachers; for myself. One of the tools available to our schools through the Iowa AEAs is the Clarity Technology and Learning Survey from BrightBytes. For the last several years Iowa schools have had the opportunity to collect data around technology use and integration in classrooms. One of the areas in which we've seen a need for improvement is using technology to create simulations, models, animations, and demonstrations. Sometimes it can be hard to find the time to look tools to use when you've probably already got some "analog" ways of thinking through this process. However, with the help of technology, kids can so easily collaborate, share, create something new, and think differently about problems! I've collected 10 tools in 8 areas to help teachers introduce some new ways to think about simulations and models in the new year!

1. Real Life Math “Make the math connection with four interactive online learning adventures for middle school classrooms. Students will enjoy these brain-boosting explorations that use digital media in innovative and creative ways. Virtual environments, simulations, videos and interactive math activities challenge and motivate students to actively engage in learning.” 2. Scratch 3. Hopscotch Learn and develop coding skills to design games, art, Rube Goldberg machines, and more 4. Loopy LOOPY can give you not just the software tools, but also the mental tools to understand the complex systems of the world around us. 5. PhET (UC Boulder) Math & Science Simulations Search by grade level, topic, device - access teaching resources such as designing for the K-12 classroom. Examples: 6. Tinkercad Free 3D Design Software with teacher resources, tutorials, and projects and challenges. For example, how to teach math with Tinkercad. Your work can even be sent to a 3D printer! Also, now a circuit simulator! 7. Sketchup Free 3D modeling software that lets you design and create - think architecture, engineering, interior design, etc. 8. Toontastic by Google Draw, animate, and narrate 3D cartoons 9. StopMotion Studio 10. PicPac Create stop motion animation and time lapse videos Stop Motion Studio: App Store Google Play For Chart View, click here. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed